| March 2023 |

Briggs and Kodnani (2023) (Goldman Sachs) |

+1.5% |

“We estimate that widespread adoption of generative AI could raise overall labor productivity growth by around 1.5pp/year (vs. a recent 1.5% average growth pace), roughly the same-sized boost that followed the emergence of prior transformative technologies like the electric motor and personal computer.” |

| May 2023 |

Baily, Brynjolfsson, and Korinek (2023) |

+2.8% |

“The projection labeled “Level” assumes that generative AI raises the level of productivity and output by an additional 18% over ten years, as suggested by the illustrative numbers we discussed for the first channel. After ten years, growth reverts to the baseline rate. The third projection labeled “Level+Growth” additionally includes a one percentage point boost in the rate of growth over the baseline rate, resulting from the additional innovation triggered by generative AI.” |

| June 2023 |

McKinsey Global Institute (2023) |

+0.1-0.6% |

“genAI alone: +0.1-0.6 pp/yr labor productivity through ~2040; combined with other tech/automation: +0.5-3.4 pp/yr.” |

| August 2023 |

Cowen (2023) (Tyler Cowen) |

+0.25%-0.5% |

“My best guess, and I do stress that word guess, is that advanced artificial intelligence will boost the annual US growth rate by one-quarter to one-half of a percentage point.” |

| March 2024 |

Korinek and Suh (2024) |

+18% |

“In the baseline AGI scenario … steady-state growth of 18% per year.” |

| April 2024 |

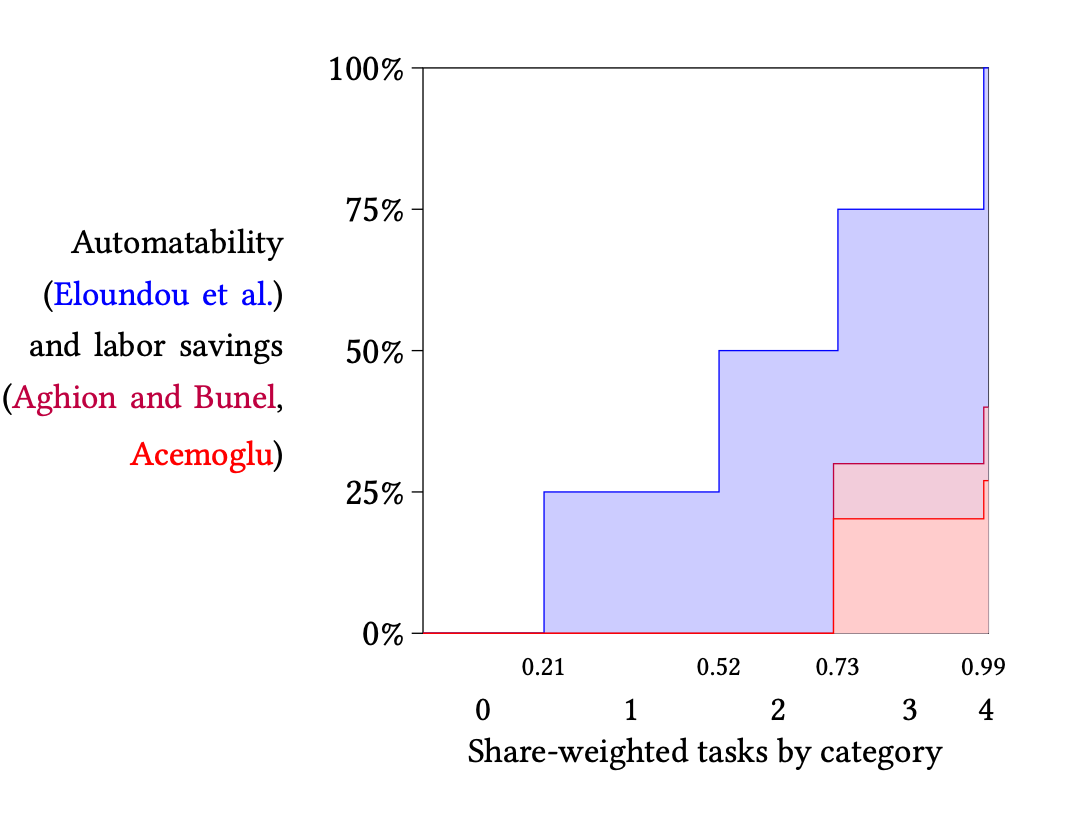

Acemoglu (2024) |

+0.07% |

“Using existing estimates on exposure to AI and productivity improvements at the task level, these macroeconomic effects appear nontrivial but modest – no more than a 0.71% increase in total factor productivity over 10 years.” |

| May 2024 |

Aldasoro et al. (2024) (BIS) |

+2.5% |

They assume a 1.5% growth in productivity but then predict that equilibrium output will increase at a higher rate. “we assume that AI raises annual productivity growth by 1.5 percentage points for the next decade, in line with plausible estimates in the literature … Growth is fastest in the first 10 years – i.e. the period in which AI directly raises industry-level TFP – at which point GDP is almost 30% higher than it would have been without” |

| June 2024 |

Aghion and Bunel (2024) |

+0.68-1.3% |

“Based on the first approach, we estimate that the AI revolution should increase aggregate productivity growth by between 0.8 and 1.3pp per year over the next decade. Using the second approach but with our own reading of the recent empirical literature on the various components of the task-based formula, we obtain a median estimate of 0.68pp additional annual total factor productivity (TFP) growth.” |

| July 2024 |

Tytell (2024) |

+0.2-0.9% |

Exhibit 1 shows a range of estimates for increases to productivity growth rates, between 0.2% and 0.9%. |

| Dec 2024 |

Filippucci, Gal, and Schief (2024) (OECD) |

+0.25-0.6% |

“main estimates for annual aggregate total-factor productivity growth due to AI range between 0.25-0.6 percentage points (0.4-0.9 pp. for labour productivity).” |

| Jan 2025 |

Wiseman and McClements (2025) |

+3-9% |

“We expect AI will provide a 3%-9% increase to economic growth per year in the near future” |

| Feb 2025 |

Cowen (2025) (Tyler Cowen) |

+0.5% |

“I’ve gone on record as suggesting that AI will boost economic growth rates by half a percentage point a year.” |

| March 2025 |

Bergeaud et al. (2025) (ECB) |

+0.29% |

“We predict TFP gains of 2.9% in the medium run (say in the next ten years) in the euro area, equivalent to an additional 0.29 percentage points per year.” |

| March 2025 |

Erdil et al. (2025) (Epoch GATE model) |

+30% |

The website figure showing Gross World Product shows that in 2035 “default” path hits approximately a 30% annualized growth rate.

However Ege Erdil says “i don’t personally predict 30% mean annual gdp growth in the US over the next 10 years … the model does with some reasonable parameter values, but my timelines for that kind of growth are longer, and there’s model uncertainty and so on”. |

| April 2025 |

Misch et al. (2025) (IMF) |

+0.2% |

“We find that the medium-term productivity gains for Europe as a whole are likely to be modest, at around 1 percent cumulatively over five years.” |

| May 2025 |

Clark (2025) (Jack Clark) (Anthropic) |

+3-5% |

“I think my bear case on all of this is 3 percent, and my bull case is something like 5 percent.” |

| June 2025 |

Wynne and Derr (2025) (Dallas Fed) |

+0.3% |

“A more reasonable scenario might be one in which AI boosts annual productivity growth by 0.3 percentage points for the next decade.” |

| June 2025 |

Filippucci, Gal, Laengle, Schief, and Unsal (2025) (OECD) |

+0.3-0.7% |

“AI could raise annual total factor productivity (TFP) growth by around 0.3-0.7 percentage points in the United States over the next decade.” |

| June 2025 |

Filippucci, Gal, Laengle, and Schief (2025) (OECD) |

+0.4-1.3% |

“annual aggregate labour productivity growth due to AI range between 0.4-1.3 percentage points in countries with high AI exposure … In contrast, the estimated range is 0.2 to 0.8 percentage points in countries where these determinants of AI gains are less favourable (e.g. Italy, Japan).” |

| Sept 2025 |

Arnon (2025) (Penn Wharton Budget Model) |

+0.15% |

“Compounded, TFP and GDP levels are 1.5% higher by 2035.” |

| Jan 2026 |

International Monetary Fund (2026) (IMF WEO Update) |

+0.1-0.8% |

“As a result, global growth may be lifted by as much as 0.3 percentage points in 2026 and between 0.1 and 0.8 percentage points per year in the medium term, depending on the speed of adoption and improvements in AI readiness globally.” |

| Jan 2026 |

Jones and Tonetti (2026) (Jones and Tonetti) |

+0.2-0.5% (implied) |

“By 2040, output is only 4% higher than it would have been without the growth acceleration, and by 2060 the gain is still only 19%. A key reason for the slow acceleration is the prominence of”weak links” (an elasticity of substitution among tasks less than one).” |

| Feb 2026 |

Amodei (2026) (Dario Amodei) |

+5-15% |

“I can see a world where A.I. brings the developed world G.D.P. growth to something like 10, 15 percent. Five, 10, 15 — I mean there’s no science of calculating these numbers. It’s a totally unprecedented thing. But it could bring it to numbers that are outside the distribution of what we saw before.” |